Emigration from Germany: Arrival in a new world – entering and arriving are two very different things

- 11. May 2020 - Emigration, General, German-American, Germany, Hamburg, History, Knowledge, Personalities

Departing from the German emigration ports Hamburg and Bremen resp. Bremerhaven, the majority of emigrants had in mind to reach North America. A significantly smaller number departed to Brazil, Australia, Argentina, Chile and various other countries.

Bremen was the principal port of departure for emigrants from the German Rhine Provinces; Hamburg was preferred by emigrants from Northeastern German states like Mecklenbung, Prussia and the territories of today’s East and Southeast European countries. Also, there were other, smaller German emigrant ports like Szczecin (Stettin) that could not keep up with Bremen resp. Bremerhaven and Hamburg in terms of numbers.

In the USA, initially it was left to the discretion of every state itself how to deal with immigrants. The first counting of immigration numbers started in 1820. In the 1820’s, about 152,000 German immigrants entered the country, between 1840 and 1850 numbers rocketed up to 1.7 million. Between 1820 and 1920 around 5.5 million immigrants arrived from Germany. When looking at 300 years of German emigration, more than 7 million Germans started a new life in the USA. Therefore, it is no surprise that 27% of the US-American population stated to have German ancestors in 2000. The numbers or immigrants kept rising continuously and from 1880 on, immigrants from South and East Europe arrived increasingly who were regarded as “unwilling to adapt”.

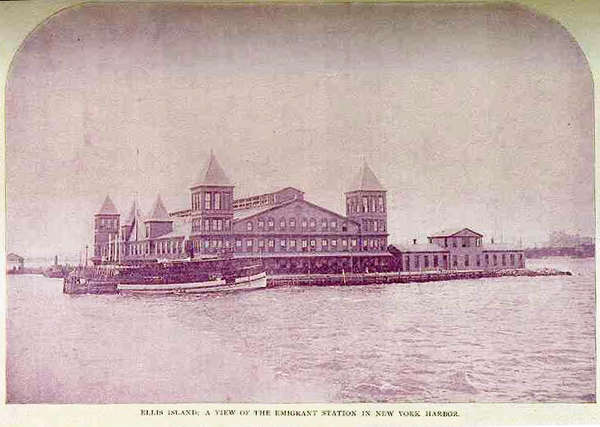

Until 1892, immigrants disembarked in Manhattan, from 1855 on via the control station Castle Clinton at the south tip of Manhattan. This station was closed in 1890 and replaced in 1892 by Ellis Island at the gates of New York. By opening the immigration station on Ellis Island, passengers were at least spared the quarantine on board before disembarkation, however, a quarantine only applied for third class passengers anyway.

At the immigration station on Ellis Island, medical inspections and questionings took place and immigrants were provided with transition accommodation. Whoever did not pass the inspections was denied entry to the United States. A general entry ban was put into force on the poor, on bigamists and polygamists, on prostitutes, on anarchists, and on Chinese in 1882; from 1907 onwards, Japanese were denied entry; and from 1917 onwards, illiterates had to return home from Ellis Island.

Since the shipping companies loaded freight on the way back to Hamburg or Bremen, the bunk beds used for the transport of third class passengers in the cargo hold below deck were taken down. Due to this double function of the ships and out of cost concerns, shipping companies were especially interested in only transporting healthy passengers. At their own expense, shipping companies had to bring back home any passengers who were denied entry because of medical or other reasons.

The process of immigration on Ellis Island could take several days and the risk to be rejected was given at any time. However, only third class passengers underwent this procedure. Those who had traveled in First or Second Class were allowed to directly cross over to Manhattan and disembark. This means, First Class passengers were spared medical and other inspections thanks to the high costs of their transport. Their fat purse and higher social rank seemingly protected these passengers from catching any disease like cholera, yellow fever, pocks, spotted fewer, or other maladies and therefore they did not pose any threat to the USA. Doesn’t this sound reasonable? You can learn more about the history of Ellis Island on site at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration.

Looking at the situation further South, immigration was not always easy, either. After gaining independence, Brazil specifically started recruiting German emigrants from 1820 onwards. The young country had a high demand on working hands. With the promise of cost-free transportation and of receiving one’s own plot, cattle and other advantages, settlers were lured to South Brazil via Bremen and Hamburg. But immigrants quickly learned about an important withheld condition upon arrival: The costs of transport had to be “worked off” before being allowed to try one’s luck as a free man in Brazil. It also happened, that travelers were held by immigration authorities and therefore never reached the planned destination. Oftentimes, being “late to receive their own plot of land”, immigrants had to sign up as a humble laborer with one of their compatriots who had become prosperous in the meantime.

When talking about immigration, Australia can be distinguished by one thing. European immigration to Australia n the beginning meant deportation or forced migration, since Australia was the penal colony of the British Empire. Germans leaving for Australia by their own free will are documented from about 1840 onwards; their main port of emigration was Hamburg. Of the 3.5 million European immigrants between 1815 and 1930, the number of Germans made up a maximum of 5%. The hopes to receive one’s own piece of land were high as well, and most of the German settlers were farmers, oftentimes winegrowers, laborers and craftsmen. The Australian strategy concerning migration especially aimed to colonize the country. This is why many German immigrants indeed had the chance to establish settlements and farms. In Barossa Valley in Southern Australia many wineries still have German names. When gold was found in the states of Victoria and New South Wales and the quest for gold began, German immigrants made up the biggest group of gold diggers. World War I brought a temporary end to German immigration to Australia: until 1925 Germans were generally denied entry and some German settlers and their descendents were expelled from the country. The German-Australian relationship finally normalized after World War II.

Apart from these many uncertainties, many of the reasons and motives to emigrate were worth the trouble. Countless German Mennonites from Russia were able to exercise their religious freedom in Paraguay and, up to the end of World War I, in Canada. They were even allowed to operate their own private schools, and Paraguay attributed other advantages to the Mennonite communities like a free right of succession and the exemption from military service. Also, settlers in Dobruja, a coastal area on the Black Sea in today’s Romania and Bulgaria which belonged to the Ottoman Empire until the late 19th century, profited from the religious freedom that the Ottoman Empire granted its citizens.

In many parts of the world, the historic flows of migration can be traced until today, for example by German town names or homelike half-timbered houses in South America. German immigrants also left their marks in big cities like Chicago, a sister city of Hamburg.

In some of these places, the German heritage can still be witnessed at German celebrations or festivals where German brass ensembles play and German traditional costumes are presented. Some well-known beer breweries and beer brands were founded by German immigrants, like the Chinese Tsintao Brewery Company, the breweries D.G. Yuengling & Son or Pabst in the US, the US-American Budweiser and the Oktoberfest is celebrated worldwide, e.g. in Blumenau, Brazil or Cincinatti, USA as German settlers maintained this tradition.

And that is not all. Many damous celebrities worldwide have German roots. Moonwalker Neil Armstrong, the first billionaire in the world John D. Rockefeller, the piano maker Steinway as well as some US-American top politicians and stars and starlets are descendents of German immigrants or were German immigrants themselves.

It is interesting to notice that across generations multiple movements of emigration can be found. Some examples are: German emigrants who first emigrated to the Danish Jutland and later followed Tsarina Catherine the Great to Russia, German Mennonites who first immigrated to Russia, later to Canada and lastly to Paraguay, German immigrants in Bessarabia whomoved on to the Dobruja region on the coast of the Black Sea in the Ottoman Empire and families and descendents of German colonists in Bulgaria and Romania who followed the Heim ins Reich (“back home to the Reich”) policy of the NS-Regime and returned to Germany in the 1940’s... If initial privileges of the settlers were lost, land became rare, political circumstances changed, the status of being a minority turned from an advantage to a disadvantage – then here we go again! You can read about the rules of this game here, if you like.

Without anticipating too much we can already recommend the end of this little series on emigration: the sources you might need for your own research. Find out about the journeys of your ancestors and accompany them along the way!

0 comments